The great Russian filmmaker of Ukrainian origins Dovzhenko would make his fifth feature film, the second part of his greatest contribution to the seventh art, his Trilogy of War, a year earlier started with the extraordinary Zvenigora, and that a year later, in 1930, he would find a closing with Earth. The director, who in the previous movie had already given glimpses of intervention in his work from the initial conception, that is, the elaboration of the script, directly supervising this elaboration, in this opportunity he will no longer be a mere supervisor, but will be directly the screenwriter, acquiring, of course and with all that detail implies in a film, more authority, authorship and domain, a feature in his work that would repeat on Earth and in many of his greatest works. The director continues with a very consistent film, twinned with the predecessor, the style of the director is still fully recognizable, the doses of visual beauty, poetry, may not flow with the exuberant wildness that the initiator of the triad, but does not disappear, plus now to appeal more strongly to the humanity of its characters, is the story of a Ukrainian territory, after the World War One, a soldier returns to his country, after surviving a train accident, finding his homeland celebrating an anniversary of its freedom, and remembering suffering.

The great Russian filmmaker of Ukrainian origins Dovzhenko would make his fifth feature film, the second part of his greatest contribution to the seventh art, his Trilogy of War, a year earlier started with the extraordinary Zvenigora, and that a year later, in 1930, he would find a closing with Earth. The director, who in the previous movie had already given glimpses of intervention in his work from the initial conception, that is, the elaboration of the script, directly supervising this elaboration, in this opportunity he will no longer be a mere supervisor, but will be directly the screenwriter, acquiring, of course and with all that detail implies in a film, more authority, authorship and domain, a feature in his work that would repeat on Earth and in many of his greatest works. The director continues with a very consistent film, twinned with the predecessor, the style of the director is still fully recognizable, the doses of visual beauty, poetry, may not flow with the exuberant wildness that the initiator of the triad, but does not disappear, plus now to appeal more strongly to the humanity of its characters, is the story of a Ukrainian territory, after the World War One, a soldier returns to his country, after surviving a train accident, finding his homeland celebrating an anniversary of its freedom, and remembering suffering. We see Ukrainian territory, a strong explosion introduces us to a world where we see a mother of three children with tormented attitude, and without those mentioned children, devastated territory, where an officer supervises the surroundings, gropes a local woman. Bloody clashes follow one another, the Ukrainian rebel troops resist Russian attacks as much as they can, which even carry out offensives with gas of laughter. Timosh (Semyon Svashenko), a Ukrainian soldier, returns from the front, travels by train with other comrades of his, but the train has a terrible accident and crashes. Timosh nevertheless survives, arrives at his land, where there is uproar and parades celebrating the Ukrainian freedom, the centuries of struggle against the Russians that cost that freedom. But the clashes do not stop with the Russians, the soldier meets resistance, also a soldier of the Red Army (Georgi Khorkov), another German soldier (Amvrosi Buchma), there are calls to defend the homeland, everyone is required for the noble cause, an arsenal of workers is formed to resist. The villagers resist with pain, parents, children, husbands, all depart leaving their families, Timosh is a witness of everything. One by one the heroes of the resistance fall, they are being shot, and finally Timosh is also arrested, and is shot, but the bullets do not seem to hurt him.

We see Ukrainian territory, a strong explosion introduces us to a world where we see a mother of three children with tormented attitude, and without those mentioned children, devastated territory, where an officer supervises the surroundings, gropes a local woman. Bloody clashes follow one another, the Ukrainian rebel troops resist Russian attacks as much as they can, which even carry out offensives with gas of laughter. Timosh (Semyon Svashenko), a Ukrainian soldier, returns from the front, travels by train with other comrades of his, but the train has a terrible accident and crashes. Timosh nevertheless survives, arrives at his land, where there is uproar and parades celebrating the Ukrainian freedom, the centuries of struggle against the Russians that cost that freedom. But the clashes do not stop with the Russians, the soldier meets resistance, also a soldier of the Red Army (Georgi Khorkov), another German soldier (Amvrosi Buchma), there are calls to defend the homeland, everyone is required for the noble cause, an arsenal of workers is formed to resist. The villagers resist with pain, parents, children, husbands, all depart leaving their families, Timosh is a witness of everything. One by one the heroes of the resistance fall, they are being shot, and finally Timosh is also arrested, and is shot, but the bullets do not seem to hurt him.

The sound had already arrived to the world of cinema by the time this film was produced, The Jazz Singer (1928) probably sat the greatest revolution in the seventh art, the cinemas around the world was still defining its final audiovisual edges, the horror of the First World War seemed to be falling behind, but in the territory of the old Russian Empire, they remembered the Civil War. In this context, this film, so revered to Dovzhenko, was born as an order of the Russian authorities to commemorate that civil war's anniversary, and he, a descendant of Ukrainians, had to perform a singular task, shooting that tribute, but trying to be on par with Eisenstein, and his powerful socialist and revolutionary vein in his films, exalting the Russian glory, the glory of the mass, of the revolution, was a primordial ideological tool in the Russia of that time; a tessitura for the descendant of Ukrainians that, combined with his unparalleled sensibility, produces the considered major cinematographic contribution of his. His film begins in a similar way to Zvenigora, clear intentions and feelings from the first frame, that initial frame where there are no humans, absence of humans, only that barbed wire, stillness and then an explosion, unusual violence after a disturbing and deceptive stillness. Then the mother, hieratic, alone, looks down, surrounded by absence, absent children, terrible graphic irony, which is added to the strength displayed in that first image. Terrible ellipsis is appreciated later, the woman, with her eyes to the ground, with her solitude, in parallel to the other character, a peasant with the equine, she hits, whips implausibly to her children, in turn that he hits the beast of charge, terrible parallel that ellipsis. A rough, unusual harshness, even touch of surrealism, almost a delirium, of some scenes that make up general features of the film, which will not disappear, of a film that does not fit with a conventional war picture -or of exaltation of war values- in its guidelines, in what it portrays. We will soon observe also an advance of the domain and management, the intention of the assembly, in those first sequences, there is a close-up of an officer who looks at the space outside the camera-range, then we see a peasant woman fall lifeless in a barren land, the military write "I killed a crow; time, marvelous", this is exchanged with the lifeless body of the old woman. Then observes the officer to the sky in great backlighting, a dark poetry seems to be flowing, like somber ideas, death and its threat are already swarming. From the beginning, from that first sequence, the explosion is inserted, the entrance is generated, the absurd violence, the absurdity of this violence and dementia is plotted, there is no nexus or excuse to insert it, it is not a pamphleteer or canonical political propaganda film.

Then comes one of the key sequences of the movie, an immortal sequence of this inescapable feature film, perhaps the most powerful that this huge Russian filmmaker of Ukrainian origins shot; as many masters said, a film must be reduced in its expression, it must has proclivity to be able to be simplified. Well, that sequence could simplify and be synthetic extract of the complete film. It is the prodigious sequence of the old soldier attacked with the gas of laughter, a power that overflows, one of the most famous sequences, if the picture is at the height of Battleship Potemkin (1925), this sequence would be at the height of that on the ladder of Odessa, Dovzhenko already reached top levels. We all know how things went, Eisenstein, more dogmatic, more conventional in his style of collective revolutionary consciousness, fitted in perfectly with the moment and feel of his nation, he was embraced as the standard of Russian cinema, his Odessa ladder was adopted and exalted as the most famous and referenced sequence in the history of cinema; but Dovzhenko in his style nothing had to envy, was his own sentiment, his own feeling what flowed while extolling his homeland. Yes, in Dovzhenko we have the pride, the power of the images of Eisenstein, but with his particular sensitivity, with his distinctive approach, his unique poetry, his poetic images, there are no canons, there is not so much rigidity for that to be a product of propaganda -of course, Eisenstein's film is much more than just that-, there is something else, there is one more level in those images, there is art, art that comes before everything, in his cinema, art, sensitivity seem to go beyond all other intentions, cinema is an art above all in him. The infinite absurd is embodied with heartbreaking realism in the aforementioned sequence, the gas of laughter that unleashes the soldier's laughter in the midst of the corpses, corpses morbidly crowned with ominous smiles, the enemy arrives, armed, does not shoot, hesitates, "where Is the enemy? ", he asks; is pathetic, powerful symbolism, much of the film is contained there, probably the most important and significant, sharpest and most acute sequence of the entire film. Another sequence, that of the train about to crash, is also exemplary of Ukrainian folklore, the accordion, a very representative element of the town before part of the Russian Empire, an element impossible to miss, especially in a cinema that lives from the image, like that of Dovzhenko, the image has expressiveness in him, both in this case, as well as with equines, abundantly displayed, in various situations, often in the field, also in war situations. Over the war, or to exalt what the chimerical glory that something like war can arouse, the film exalts its nation. We have a sequence that expresses that, an old man, through tears, a citizen calling, summoning his people, the people of Ukraine, teachers, workers, artists, we are talking about three hundred years of yoke, pride, the fatherland, dignity, the nation, elements that put him at the level of the other masters of the Soviet cinema, Eisenstein, Vertov, Pudovkin. He shares with them the feeling of his cinema, of his land, but Dovzhenko always lets the images speak, there is little text, the horror and pain of war are the transmitters, he strips his vision of the greatest partisan rigidity, even proselytizing, that could have the movies of his comrades. It is interesting that there are almost no characters, in this film, with respect to Zvenigora, that element loses individuality, the invaders dehumanize in their collectivism, in the mass they represent, there are no faces; but there is more feeling, the filmmaker prints more feeling in counterbalance, some consider for that reason this film as the cusp work of the director, and of course, he would also sit school, leave influence in subsequent filmmakers, who continued his poetic audiovisual imprint.

Then comes one of the key sequences of the movie, an immortal sequence of this inescapable feature film, perhaps the most powerful that this huge Russian filmmaker of Ukrainian origins shot; as many masters said, a film must be reduced in its expression, it must has proclivity to be able to be simplified. Well, that sequence could simplify and be synthetic extract of the complete film. It is the prodigious sequence of the old soldier attacked with the gas of laughter, a power that overflows, one of the most famous sequences, if the picture is at the height of Battleship Potemkin (1925), this sequence would be at the height of that on the ladder of Odessa, Dovzhenko already reached top levels. We all know how things went, Eisenstein, more dogmatic, more conventional in his style of collective revolutionary consciousness, fitted in perfectly with the moment and feel of his nation, he was embraced as the standard of Russian cinema, his Odessa ladder was adopted and exalted as the most famous and referenced sequence in the history of cinema; but Dovzhenko in his style nothing had to envy, was his own sentiment, his own feeling what flowed while extolling his homeland. Yes, in Dovzhenko we have the pride, the power of the images of Eisenstein, but with his particular sensitivity, with his distinctive approach, his unique poetry, his poetic images, there are no canons, there is not so much rigidity for that to be a product of propaganda -of course, Eisenstein's film is much more than just that-, there is something else, there is one more level in those images, there is art, art that comes before everything, in his cinema, art, sensitivity seem to go beyond all other intentions, cinema is an art above all in him. The infinite absurd is embodied with heartbreaking realism in the aforementioned sequence, the gas of laughter that unleashes the soldier's laughter in the midst of the corpses, corpses morbidly crowned with ominous smiles, the enemy arrives, armed, does not shoot, hesitates, "where Is the enemy? ", he asks; is pathetic, powerful symbolism, much of the film is contained there, probably the most important and significant, sharpest and most acute sequence of the entire film. Another sequence, that of the train about to crash, is also exemplary of Ukrainian folklore, the accordion, a very representative element of the town before part of the Russian Empire, an element impossible to miss, especially in a cinema that lives from the image, like that of Dovzhenko, the image has expressiveness in him, both in this case, as well as with equines, abundantly displayed, in various situations, often in the field, also in war situations. Over the war, or to exalt what the chimerical glory that something like war can arouse, the film exalts its nation. We have a sequence that expresses that, an old man, through tears, a citizen calling, summoning his people, the people of Ukraine, teachers, workers, artists, we are talking about three hundred years of yoke, pride, the fatherland, dignity, the nation, elements that put him at the level of the other masters of the Soviet cinema, Eisenstein, Vertov, Pudovkin. He shares with them the feeling of his cinema, of his land, but Dovzhenko always lets the images speak, there is little text, the horror and pain of war are the transmitters, he strips his vision of the greatest partisan rigidity, even proselytizing, that could have the movies of his comrades. It is interesting that there are almost no characters, in this film, with respect to Zvenigora, that element loses individuality, the invaders dehumanize in their collectivism, in the mass they represent, there are no faces; but there is more feeling, the filmmaker prints more feeling in counterbalance, some consider for that reason this film as the cusp work of the director, and of course, he would also sit school, leave influence in subsequent filmmakers, who continued his poetic audiovisual imprint. Above what should pay tribute to the Russian Civil War, Dovzhenko prefers to pay tribute to freedom, to the human being, before the war portrays the evils it generates, the suffering of the people, human suffering, that's what he exalts; exalts it by deploring it, exalts it in his cinematic world, a world where a mother has no children, where he beats them allegorically to a man who hits a horse, where the first thing we see is something that explodes without cause. It is the history of Ukraine, and therefore of an empire, the Russian empire, of course, indivisible participation have the Bolsheviks, who come into action, workers, trade unions, Soviet history and their inescapable collective feeling, in this opportunity with some distance from Ukraine. And of course, the collective struggle is a feature of Russia, a trait of which is not exempt any artist of the time, the struggle, the resistance that represents that arsenal where the last glimmers of Ukrainian rebellion are stored, which has its core figure in Timosh, a figure that is shown at an already superhuman level, since his appearance, with his face shown in moments without the slightest disarray, rather well-dressed, contrasted with the dirty, sweaty and disheveled faces of his comrades. From his first appearances, even after the train crashed, and all his comrades died, Timosh jokes about his survival in the accident, already is slipped the nature of him that will be confirmed in the end, he is more than a soldier, he is the resistance. And of course, he is more than a human in Dovzhenko's history, he has transcended that mere condition, he is now a complete nation, he is now a feeling, an idea, an ideal that will not die with bullets, that extraordinary ending portrays him to us as invulnerable, huge final sequence in which the feeling of a nation is expressed, of a freedom that can not be violated, which is, like Timosh, undamaged by bullets. A dark atmosphere reminds us again of the strong dose of expressionism that the filmmaker printed to his works, in the end we find a sequence that stands out, the successive executions of the members of the resistance, the shadows that flow deformed in the executions, moments of fatal dementia, awakens that echo of expressionism; however, the uncontainable expressionist delirium that was paraded in Zvenigora will leave room for something more now, to focus more on the exaltation of the Ukrainian people, without leaving aside the gloomy tonality, and for moments of madness and almost onirism, as when the equine responds to the human his hits with words. Apart from the visual difference just mentioned between the initial film of the trilogy and the one now commented, it is irrefutable to point out that they are full-lenght films totally twinned, consistent, concise their unity, they are part of a whole, if one stood out more poetry and visual strength, they share edges, at the level of sensitivity and also at a technical level, details such as montage, exaltation of their land, national pride, and this film surpasses its predecessor in appealing precisely to human sentiment. For the rest, in those powerful sequences of great montage we will appreciate the other audiovisual resources, high-angle shots, low-angle shots, shadows and warm expressionist halos. The overlays of images, and of sequences, which was part of an extraordinary sequence in Zvenigora -the aforementioned expressionist halo-, now will not appear, they do it in dribs and drabs, in a film where we will often observe hieratic interpretations, symbolizing absence, as Ukrainian women and men at certain times, they lack something, the war takes away some humanity. As mentioned, Dovzhenko once again teaches a master class of assembly, a key element in this trilogy and in the previous film, evidence that is one of the distinguishing points of his cinema, a dominance in the subject. The sequence of train crash is one of the most obvious in this sense, a cathedra of assembly, capturing despair, anguish, compressing and dilating the times, adding haste. Deepening on what was said before, that is one of the major features of the film, the ambiguity, which plagues the whole film, because as it was said, being a commission from Russian authorities, it exalts the Ukrainian dignity, but more than that, rather than taking one side, highlights the absurdity of the war. Even the soldiers of one side and another are not visually well differentiated, the clarity in intention or strict affiliation in that sense of the filmmaker is not as vigorous as the portrayal of misery and absurdity, it does not take sides as strongly as it exalts the nonsense of this, the suffering; it is more a hymn against the war, it is art over other things, it is what sets him apart from the other Russian authors, so close but at the same time so distant with the cinema of this giant. And that is what the gratuitous violence seen from the beginning collaborates with, explosions, crudeness, there is no conventional exaltation of the values of the war defense, there is no military pride, is another the director's via. The trilogy continued its way, a compendium of cinema until then, of expressionism, of Russian montage, of feeling, the Russian collective identity also, an epitome of all the virtues of silent cinema in its twilight manifested in the filmmaker as a sublime farewell, because the sound was already coming with The Jazz Singer. The following year, Dovzhenko would complete his great triptych, filming Earth (1930), but for many, his artistic peak had arrived, Arsenal had seen the light, cataloged as the greatest cinematographic achievement of this audiovisual poet, a film more than necessary.

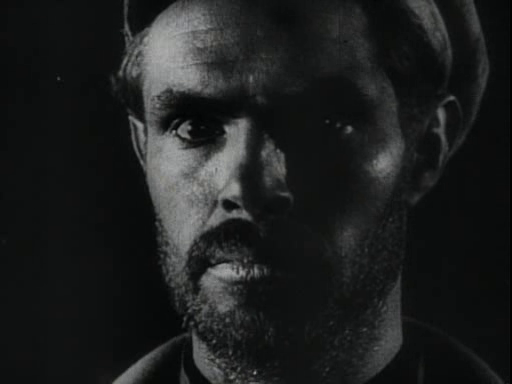

Above what should pay tribute to the Russian Civil War, Dovzhenko prefers to pay tribute to freedom, to the human being, before the war portrays the evils it generates, the suffering of the people, human suffering, that's what he exalts; exalts it by deploring it, exalts it in his cinematic world, a world where a mother has no children, where he beats them allegorically to a man who hits a horse, where the first thing we see is something that explodes without cause. It is the history of Ukraine, and therefore of an empire, the Russian empire, of course, indivisible participation have the Bolsheviks, who come into action, workers, trade unions, Soviet history and their inescapable collective feeling, in this opportunity with some distance from Ukraine. And of course, the collective struggle is a feature of Russia, a trait of which is not exempt any artist of the time, the struggle, the resistance that represents that arsenal where the last glimmers of Ukrainian rebellion are stored, which has its core figure in Timosh, a figure that is shown at an already superhuman level, since his appearance, with his face shown in moments without the slightest disarray, rather well-dressed, contrasted with the dirty, sweaty and disheveled faces of his comrades. From his first appearances, even after the train crashed, and all his comrades died, Timosh jokes about his survival in the accident, already is slipped the nature of him that will be confirmed in the end, he is more than a soldier, he is the resistance. And of course, he is more than a human in Dovzhenko's history, he has transcended that mere condition, he is now a complete nation, he is now a feeling, an idea, an ideal that will not die with bullets, that extraordinary ending portrays him to us as invulnerable, huge final sequence in which the feeling of a nation is expressed, of a freedom that can not be violated, which is, like Timosh, undamaged by bullets. A dark atmosphere reminds us again of the strong dose of expressionism that the filmmaker printed to his works, in the end we find a sequence that stands out, the successive executions of the members of the resistance, the shadows that flow deformed in the executions, moments of fatal dementia, awakens that echo of expressionism; however, the uncontainable expressionist delirium that was paraded in Zvenigora will leave room for something more now, to focus more on the exaltation of the Ukrainian people, without leaving aside the gloomy tonality, and for moments of madness and almost onirism, as when the equine responds to the human his hits with words. Apart from the visual difference just mentioned between the initial film of the trilogy and the one now commented, it is irrefutable to point out that they are full-lenght films totally twinned, consistent, concise their unity, they are part of a whole, if one stood out more poetry and visual strength, they share edges, at the level of sensitivity and also at a technical level, details such as montage, exaltation of their land, national pride, and this film surpasses its predecessor in appealing precisely to human sentiment. For the rest, in those powerful sequences of great montage we will appreciate the other audiovisual resources, high-angle shots, low-angle shots, shadows and warm expressionist halos. The overlays of images, and of sequences, which was part of an extraordinary sequence in Zvenigora -the aforementioned expressionist halo-, now will not appear, they do it in dribs and drabs, in a film where we will often observe hieratic interpretations, symbolizing absence, as Ukrainian women and men at certain times, they lack something, the war takes away some humanity. As mentioned, Dovzhenko once again teaches a master class of assembly, a key element in this trilogy and in the previous film, evidence that is one of the distinguishing points of his cinema, a dominance in the subject. The sequence of train crash is one of the most obvious in this sense, a cathedra of assembly, capturing despair, anguish, compressing and dilating the times, adding haste. Deepening on what was said before, that is one of the major features of the film, the ambiguity, which plagues the whole film, because as it was said, being a commission from Russian authorities, it exalts the Ukrainian dignity, but more than that, rather than taking one side, highlights the absurdity of the war. Even the soldiers of one side and another are not visually well differentiated, the clarity in intention or strict affiliation in that sense of the filmmaker is not as vigorous as the portrayal of misery and absurdity, it does not take sides as strongly as it exalts the nonsense of this, the suffering; it is more a hymn against the war, it is art over other things, it is what sets him apart from the other Russian authors, so close but at the same time so distant with the cinema of this giant. And that is what the gratuitous violence seen from the beginning collaborates with, explosions, crudeness, there is no conventional exaltation of the values of the war defense, there is no military pride, is another the director's via. The trilogy continued its way, a compendium of cinema until then, of expressionism, of Russian montage, of feeling, the Russian collective identity also, an epitome of all the virtues of silent cinema in its twilight manifested in the filmmaker as a sublime farewell, because the sound was already coming with The Jazz Singer. The following year, Dovzhenko would complete his great triptych, filming Earth (1930), but for many, his artistic peak had arrived, Arsenal had seen the light, cataloged as the greatest cinematographic achievement of this audiovisual poet, a film more than necessary.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario